Penal Code Kenya Pdf Download

tina.law

Leader Member

- Joined

- Mar 26, 2018

- Messages

- 142

- Reaction score

- 86

- Points

- 28

- Location

- Kochi (Cochin)

- Gender

- Female

PENAL CODE CHAPTER 63 LAWS OF KENYA. LAWS OF KENYA PENAL CODE CHAPTER 63 Revised Edition 2014 2012 Published by the National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General www.kenyalaw.org CHAPTER 63 PENAL CODE ARRANGEMENT. More information.

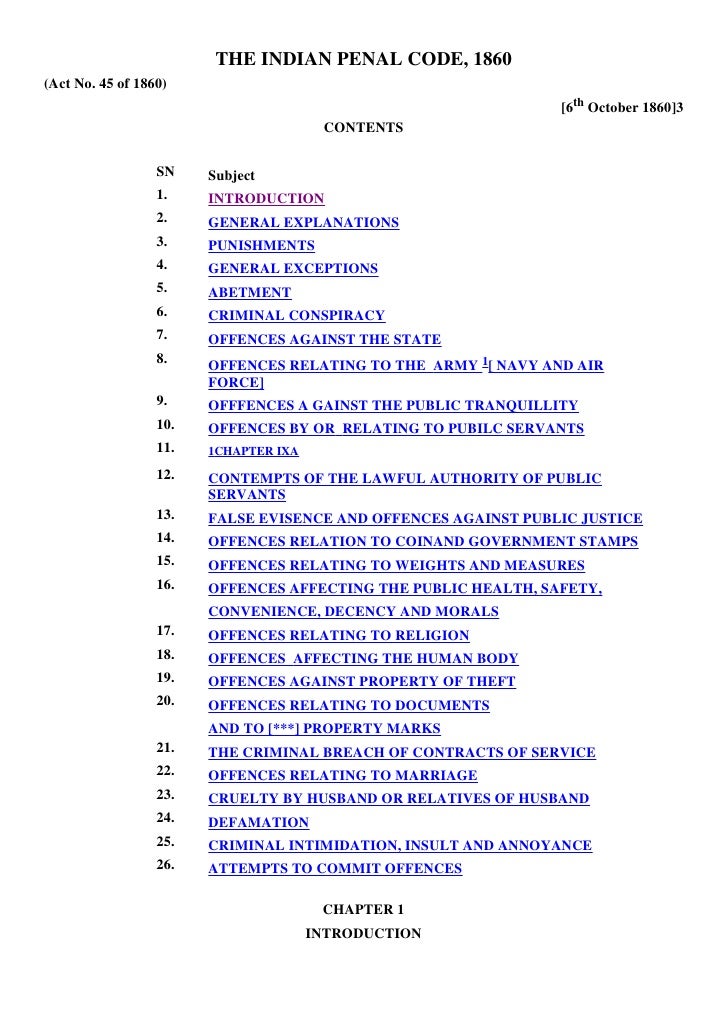

Hi Fellow Law (LLB) Students,On this thread, I am sharing brief and concise notes on the Law First Year Subject - IPC (Indian Penal Code). These PDF lecture notes will help you in preparing well for your semester exams on IPC (Indian Penal Code) and assist you in studying from ready made lecture notes.

The major topics covered in these lecture notes and eBook of IPC (Indian Penal Code) are:

- Definitions, General exceptions

- Abetment, Unlawful assembly, etc.

- False evidence, Culpable homicide and murder

- Hurt, grievous hurt, Wrongful restraint

- Criminal force and assault, Kidnapping, Abduction

- Theft, Extortion, Robbery and Dacoity

- Criminal Misappropriation, Cheating, Mischief

- Criminal Tresspass and house breaking, Forgery

- Rape, Adultery, Bigamy, Defamation, Criminal Intimidation

(Feb. 14, 2017) On February 6, 2017, the Constitutional and Human Rights Division of the High Court of Kenya at Nairobi found unconstitutional article 194 of the country’s 1930 Penal Code, which relates to criminal defamation. (Jacqueline Okuta & another v Attorney General & 2 others [2017] eKLR, Kenya Law website.) Two individuals, Jacqueline Okuta and Jackson Njeru, who were on two separate occasions each arraigned on criminal defamation charges for posting items on the Facebook page Buyer beware-Kenya, brought the petition challenging the legality and continued enforcement of the provision. (Id. at 2.) The challenge relied on two provisions of the 2010 Kenyan Constitution: the freedom of expression clause and the limitation of rights and fundamental freedoms clause. (Id. at 3; The Constitution of Kenya (2010), §§ 24 & 33, Embassy of the Republic of Kenya, Washington D.C.website.)

The Penal Code

The Penal Code states, “[a]ny person who, by print, writing, painting or effigy, or by any means otherwise than solely by gestures, spoken words or other sounds, unlawfully publishes any defamatory matter concerning another person, with intent to defame that other person, is guilty of the misdemeanour termed libel.” (Penal Code of 1930, art. 194, Cap. 63 (Aug. 1, 1930), Kenya Law website.) The Code defines the term “defamatory matter” as a “matter likely to injure the reputation of any person by exposing him to hatred, contempt or ridicule, or likely to damage any person in his profession or trade by an injury to his reputation; and it is immaterial whether at the time of the publication of the defamatory matter the person concerning whom the matter is published is living or dead.” (Id. art. 195.) The general punishment imposed on conviction for a misdemeanor, including defamation, is a maximum of two years in prison and/or a fine. (Id. art. 36.)

The Constitutional Provisions on Freedom of Expression

The Bill of Rights chapter in the 2010 Kenyan Constitution includes a freedom of expression clause. The first part of this clause states, ”[e]very person has the right to freedom of expression, which includes … [the] freedom to seek, receive or impart information or ideas; … freedom of artistic creativity; and … academic freedom and freedom of scientific research.” (The Constitution of Kenya, art. 33(1).)

However, this right is not absolute. The second part of the same constitutional provision imposes a limitation on the right to freedom of expression by limiting its application in certain instances. More specifically, this right to freedom of expression cannot be invoked to protect expression relating to war propaganda, incitement of violence, or hate speech or advocacy of hatred, including ethnic incitement. (Id. art. 33(2).) Further, the provision states, ”[i]n the exercise of the right to freedom of expression, every person shall respect the rights and reputation of others.” (Id. art. 33(3).)

The limitation of the rights and fundamental freedoms clause stipulates further limitations on freedom of expression and restrictions on the manner in which such limitations may be put in place. It states:

(1) A right or fundamental freedom in the Bill of Rights shall not be limited except by law, and then only to the extent that the limitation is reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom, taking into account all relevant factors, including––

(a) the nature of the right or fundamental freedom;

(b) the importance of the purpose of the limitation;

(c) the nature and extent of the limitation;

(d) the need to ensure that the enjoyment of rights and fundamental freedoms by any individual does not prejudice the rights and fundamental freedoms of others; and

Surviving high school pc game free download. (e) the relation between the limitation and its purpose and whether there are less restrictive means to achieve the purpose.

(2) Despite clause (1), a provision in legislation limiting a right or fundamental freedom—

(a) in the case of a provision enacted or amended on or after the Constitution of Kenya effective date, is not valid unless the legislation specifically expresses the intention to limit that right or fundamental freedom,and the nature and extent of the limitation;

(b) shall not be construed as limiting the right or fundmental freedom unless the provision is clear and specific about the right or freedom to be limited and the nature and extent of the limitation; and

(c) shall not limit the right or fundamental freedom so far as to derogate from its core or essential content.

(3) The State or a person seeking to justify a particular limitation shall demonstrate to the court, tribunal or other authority that the requirements of this Article have been satisfied. (Id. art. 24.)

The Ruling

At the outset of its ruling, the Court noted that most rights and freedoms that citizens enjoy are not absolute in nature and that such rights are “subject to limitations that are necessary and reasonable in a democratic society for the realization of certain common good such as social justice, public order and effective government or for the protection of the rights of others.” (Jacqueline Okuta & another v Attorney General & 2 others, supra.)

The issue in the case revolved around the instances and the degree to which the rights may be limited. On this, the Court noted that restrictions on freedom of speech must be limited to the prevention of “the expression of thought which is intrinsically dangerous to public interest and [nothing else].” (Id.) The Court found that criminal defamation does not fall into that category because it “aims to protect individual interests” and not that of the public. (Id.) The Court further noted that a “common way” for ascertaining whether a limitation imposed on a fundamental right or rights is warranted is by undertaking the proportionality test. (Id.) It outlined a four-prong proportionality test developed by a number of authors under which a limitation would be permissible. These are:

[if] (i) [the limitation] is designated for a proper purpose; (ii) the measures undertaken to effectuate such a limitation are rationally connected to the fulfilment of that purpose; (iii) the measures undertaken are necessary in that there are no alternative measures that may similarly achieve that same purpose with a lesser degree of limitation; and finally (iv) there needs to be a proper relation (“proportionality stricto sensu” or “balancing”) between the importance of achieving the proper purpose and the special importance of preventing the limitation on the constitutional right. (Id.)

However, the Court noted, even in instances where the limitation may be proportional, imposing a limitation may still be unjustified if doing so would have a severe impact on individuals or groups. (Id.)

The Court then moved to determine whether it is necessary to criminalize defamation in order to accomplish an ordinarily legitimate purpose. It split this question into two parts, one relating to the consequence of criminalization and the other to the availability of alternative remedies to dealing with defamation. (Id.) With regard to the first question, the Court found that the offence of criminal defamation, while similar to other offences in many ways, is distinctive in that it has a stifling and chilling effect on “the right to speak and the right to know.” (Id.) The Court elaborated as follows:

For example it cannot be denied that newspapers and modern communication methods play a vital role in disseminating information in every society, whether open or otherwise. Part and parcel of that role is to unearth corrupt or fraudulent activities, executive and corporate excesses, persons who are dangerous to the society and other wrongdoings that impinge upon the rights and interests of ordinary citizens. It is inconceivable that the citizens, the media and Civil Societies could perform investigative and informative functions without defaming one person or another. The overhanging effect of the offence of criminal defamation is to stifle and silence the free flow of information in the public domain. This, in turn, may result in the citizenry remaining uninformed about matters of public significance and the unquestioned and unchecked continuation of unconscionable malpractices. (Id.)

The Court further noted that the gravity of the penalty imposed for this offence adds to the severity of its effect and “is clearly excessive and patently disproportionate.” (Id.)

With regard to the second question, the Court found that the availability of a civil remedy for defamation means that criminalization of defamation does not meet one of the elements of the proportionality test, which is “[a]nother very compelling reason for eschewing resort to criminal defamation.” (Id.)

The Court then held that “the invocation of criminal defamation to protect one’s reputation is … unnecessary, disproportionate and therefore excessive and not reasonably justified in an open society based on human dignity, equality and freedom. (Id.) The Court further held that article 194 of the Penal Code is “unconstitutional and invalid to the extent that it covers offences other than those contemplated under Article 33(2)(a)-(d)” and its continued enforcement against the petitioners “would be unconstitutional and/or a violation of their fundamental right to the freedom of expression … .” (Id.)